This statement was written by Dr. Jan Beckett, whose photography and my paintings were hung in collaboration and support of the vision of KĀNEHŪNĀMOKU at the State Capital entrance January 20th through February 7, 2020. Mahalo to Kumu Glen Kila of Marai Ha’a Koa who first introduced me to the mo’olelo and wahipana of this area. I look forward to learning more about the Silva stories too.

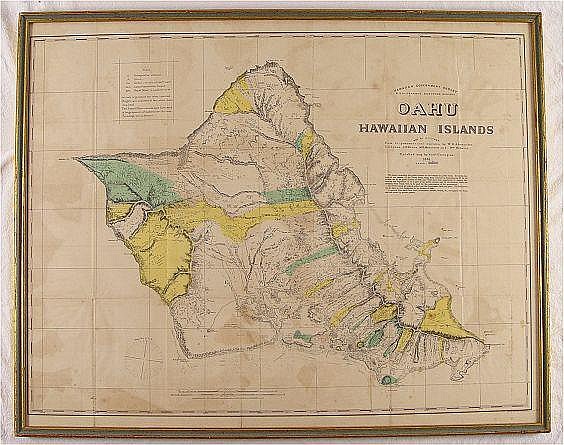

KĀNEHŪNĀMOKU: A Wai‘anae Cultural Landscape is an exhibit in memory of Albert Silva, he kupa o ka ‘āina. Kānehūnāmoku is a place name passed down in certain Wai‘anae families. It describes the area from Kepuhi Point to Ka‘ena Point, including the land sections of Kea‘au, ‘Ōhikilolo, Ko‘iahi, Mākua, Kahanahāiki, Keawa‘ula, Kuaokalā and Ka‘ena. Families with ancestral ties to that cultural landscape hope to see it permanently set aside as a pu‘uhonua, a place of healing and refuge for Hawaiian ‘ohana, keiki and others. The Wai’anae Sustainable Plan expresses the will of the community, that there be no development past Kephi Point – that is, from Kepuhi Point to Ka‘ena Point. This exhibit honors that vision. Driving past Kea‘au Beach Park, one sees little but a shoreline and pasture filled with kiawe, a tree brought in to feed cattle. We see in our minds a Native Hawaiian dryland forest reestablished, with stands of kou, wiliwili, ‘iliahi and lama. We see an understory of plants original to that place, plants such as a‘ali‘i and ‘ilima. On the kahakai side of the road, we see stands of milo and ground cover such as pa‘uohi‘iaka. We see a carefully managed marshery that allows near-shore species to flourish. In the uplands of Kau-lu, the watershed for a stream that is now dry, we see a native upland forest reestablished, so that water once again flows, and so that the birds of the uplands – such as ‘amakihi – return to their habitats. And it is here in this sacred landscape that cultural practitioners see past Nihoa and Mokumananana, to kilo the floating islands beyond the horizon. A cultural landscape exists in the interconnections among people, among people and their environment, and among various natural elements of the environment: plants, insects, marshes, birds, rain, water flow and winds.

A cultural landscape validates the cultural knowledge embedded in Native Hawaiian ‘ohana (families), mo‘olelo (oral literature) and ‘olelo (language). The work needed to recreate that landscape functions as pilina, to bring families closer together, to heal those caught in cycles of drugs and violence and to provide a safe environment where keiki can learn culture, ‘olelo and history. It can also function as a sustainable source of food, helping to promote healthy diets and traditional ways of life. Kupuna Albert Silva, who recently passed away, told the story that the name ‘Ōhikilolo (crazy crab) comes from periodic migrations of hundreds of crabs across the road, away from the beach. We hope to see the migration again one day.

If this seems like an unreachable goal, think of the success of the Natural Area Reserve at Ka‘ena, just down the road. Or think of the amazing success in replanting native plant colonies on Kaho‘olawe, aided by upland catchment systems. It can be done in Kānehūnāmoku as well.